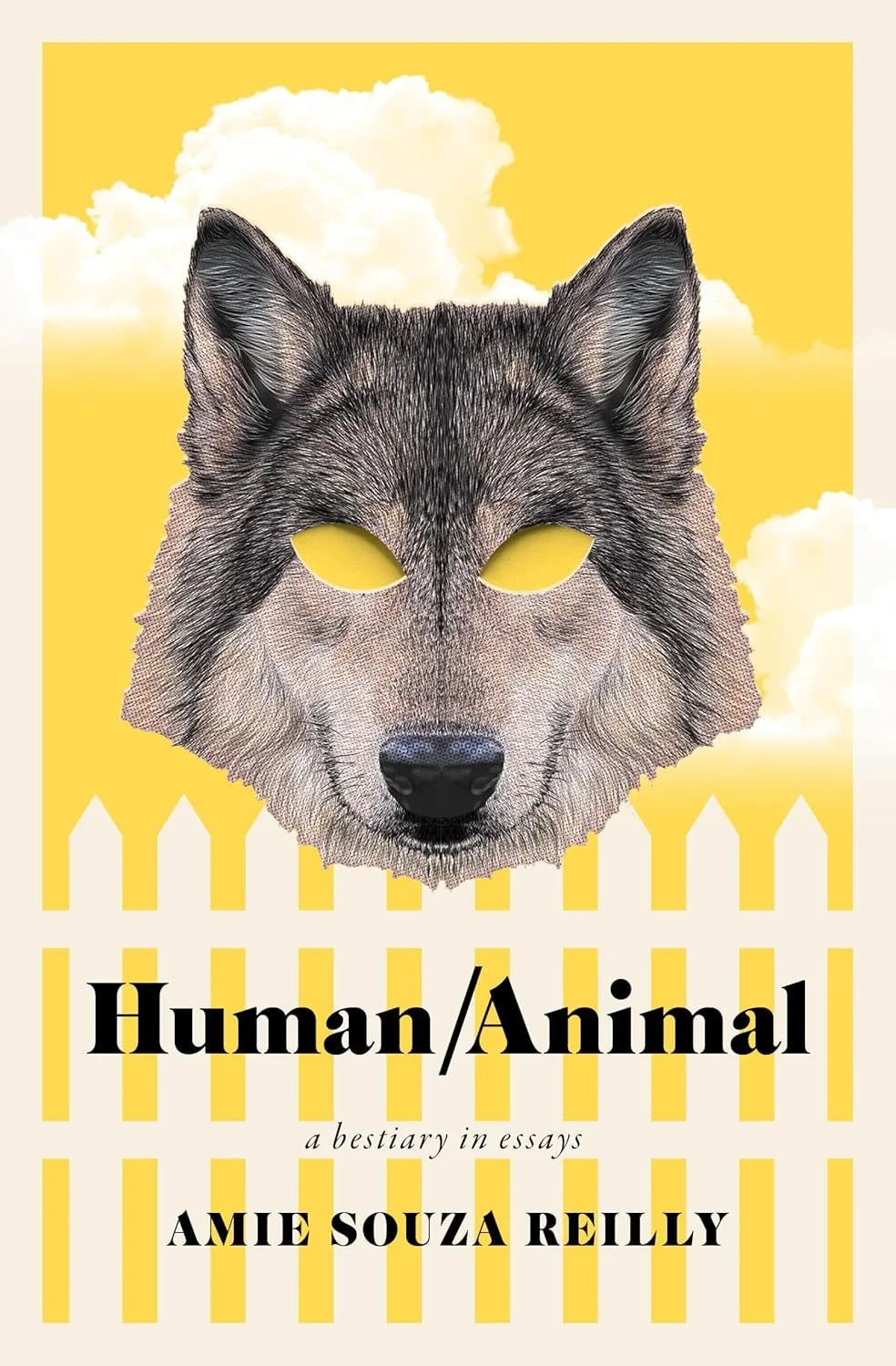

Barrelhouse Reviews: Human/Animal by Amie Souza Reilly

Reviewed by Rebecca Hussey

Wilfrid Laurier University Press / April 2025 / 216 pp

Buying a new house is an iconic American moment: it’s a chance to start over, to recreate one’s life, to have new space—probably more space—within and around which to shape the self. It’s a moment full of hope and dreams. But what happens when the neighbors turn out to be a nightmare?

Amie Souza Reilly’s Human/Animal: A Bestiary in Essays takes this broken dream as its starting point. She turns a disaster into a wide-ranging, nuanced exploration of another iconic American experience: living under the threat of violence. The neighbors in question are brothers who lost the chance to buy Reilly’s new suburban Connecticut house for themselves and want to make her, her husband, and their son pay. They do everything they can to make the family feel vulnerable, from staring in windows and marching unwelcome through their yard to trapping Reilly and her son in their car and screaming at them. Other neighbors sympathize but have little else to offer, and the police prove condescending and ineffectual. The brothers know precisely how to be as menacing as possible without breaking any laws, and there is little the family can do.

Mixing memoir, research, essay, and original art, Reilly connects violence to questions of language, identity, and boundaries. What happens to the self when its physical and psychic borders are threatened? What does it mean to own property in a country founded on stolen land? How does language embody and reflect the violence at the heart of American culture, and why is that language so often linked to the animal world?

Living with threats of violence, for Reilly, extends into every aspect of life, from the personal to the national. Human/Animal embodies this wide-ranging theme in its form, moving back and forth between personal narrative and discussions of books and films that shed light on the story. Books such as Eula Biss’s On Immunity, Carol J. Adams’s The Sexual Politics of Meat, Virginia Despentes’s King Kong Theory, among many others, and horror films such as Halloween and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre help connect what might be one family’s idiosyncratic experience to larger cultural concerns.

Reilly’s animal drawings unify the whole. Sprinkled throughout the text, these drawings bring to life the unique place animals hold in our imaginations. Each animal—bear, bat, chicken, monkey, parrot, peacock, pig—carries both literal and symbolic meaning. We see the actual animal in Reilly’s exquisite line drawings, so that the living, breathing creatures inhabit the pages. At the same time, Reilly notes that many animal names carry other meanings, often clustering around ideas of harm, labor, and mothering.

The English language, like the English colonialism that spread to America, is full of brutality. So then, using animal names to mean verbs of harm, labor, and mothering becomes a metaphor and an analogy for the power baked into our white patriarchal imperialist society, with its violence, destructive capitalist practices, and its laws and medical policies that do very little to support mothers.

Each animal provides a lens through which to explore both the brothers’ threats and the danger that exists more broadly for women, people of color, and anyone else who is vulnerable and powerless.

The essay “On Performance,” for example, is subtitled “to cow/to cock/to clam,” and considers the way public displays of power can “cow” its audience and make them “clam up.” Reilly recounts the time one of the brothers followed Reilly’s husband Matt on the train and made a fake phone call in which he loudly described Matt’s family within his hearing. It was a bizarre and self-conscious performance of knowledge and intimacy meant to unsettle, and Reilly responds with embarrassment and shame at their inability to stop the brothers’ intrusions. The chapter moves on to discuss performance as art, looking at Marina Abramović’s Rhythm O and Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Mouth to Mouth, both of which explore ideas about bodily display, power, and control. On the one hand, the brother’s performance “was one of loud power, an act that drew attention to himself as a person of stature, a dominant force we could not ignore.” On the other, “Often, performance art, especially in pieces created by female artists, pushes back against silencing.” The cow, the clam, and the cock (the animal, but also the sense of swaggering and bragging) become sites of struggle over who dominates whom, who is heard and who has to listen. The tension is embodied in the words themselves.

Other essays explore boundaries, gossip, and revenge. One, on fear, examines horror films alongside the fear lurking in exclusionary white suburbs, and Reilly’s own fear of her neighbors: “My fear is mine and is also part of a collective consciousness, held by many folks living outside of a cisgendered straight White male identity…Like an electrical undercurrent to our existence, the longer it’s felt, the more we grow accustomed to it.” This chapter is subtitled “to hawk,” meaning “to pursue or attack while flying,” as well as “to sell.” Intertwined in this section are the lure of home ownership – the safety and security owning property is supposed to bring—and the reality that not only is this safety an illusion, it’s an illusion founded on America’s history of racism and colonialism. As Reilly puts it, “Suburbs have been created through displacement, racism, and misogyny. No wonder so many horror films take place there.”

In considering questions that are important at any time but feel particularly pressing in this era of backlash against efforts to grapple with sexism and racism, Human/Animal is a valuable contribution to a tradition of writing that is both personal and critical. It fits comfortably on a shelf with Maggie Nelson’s The Argonauts, Marianne Booker’s Intervals, and Nuar Alsadir’s Animal Joy, all books that defy genre in an attempt to demonstrate the interwoven nature of story and idea, of the personal and the political, of anecdote and philosophy. It’s an honest, searching look at the violence that lurks in our houses, our neighborhoods, and our language.

Rebecca Hussey is a board member of the National Book Critics Circle. Her writing has appeared in Words Without Borders, The Kenyon Review, and Full Stop, among others, and she is a co-host of the One Bright Book podcast. She teaches English at Connecticut State Community College Norwalk.