Barrelhouse Reviews: What to Carry Into the Future by Susan Landers

Reviewed by Gina Myers

Roof Books / March 2025 / 106 pp

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit the United States, many people began to reassess their relationships to work. How much time, energy, and effort do they give to something that doesn’t love them back? “Burnout” became a phrase people used to describe what they felt at work, rather than a personal insult. The idea that we as a society have been doing something very wrong when it comes to work-life balance was already bubbling to the surface before the pandemic, as evident in the popularity of, for instance, Jenny Odell’s How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy. And What to Carry Into the Future, a new collection of poetry by Sue Landers, is also on the leading edge of this growing anti-work sentiment. Composed of poems written between 2017 and 2024, What to Carry Into the Future documents a poet quitting her job to slow down and pay attention. What she sees—the good and the bad—Landers generously shares with us in this complicated love letter to New York City.

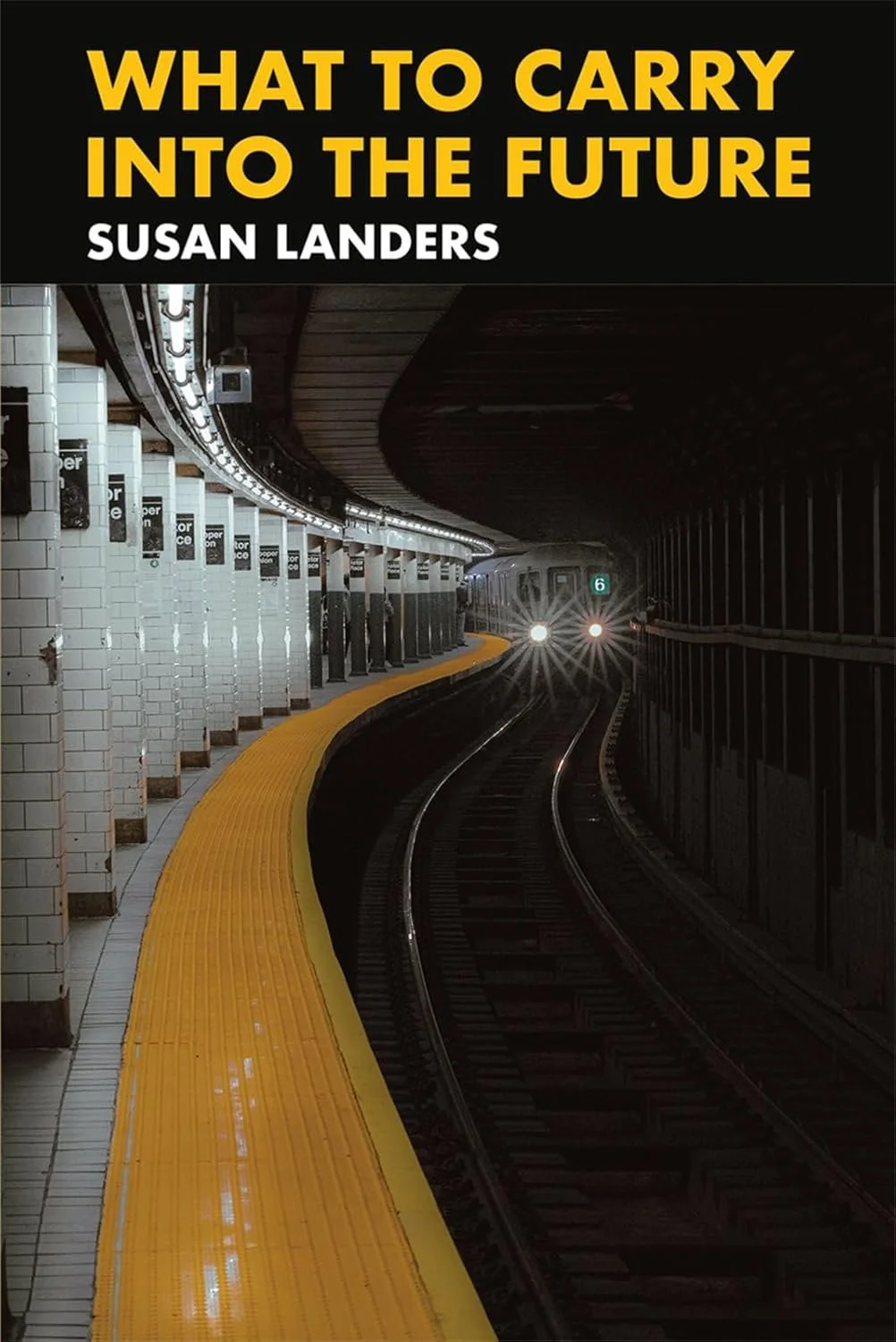

What to Carry Into the Future invites the reader on a journey through the wilderness and wildness of the Big Apple. The book is divided into three long poem cycles, each charting a specific map of the city: riding every subway line from end-to-end, observing vegetation along the city’s sidewalks, and exploring the waterways that move through and around the five boroughs. The book opens with an epigraph from Rebecca Solnit: “What we call a city is a succession of wildly different places in the same location.” The first poem, “My Quotidian Icon,” takes us to these places. In the poem, Landers has quit her job “to write poems / about a subway / everyone hates because / they have to take it / to work every day.” Each page is marked with the subway line she rides. The poem ends on a note anyone who has relied on public transit can appreciate. While Landers waits for a Z train to arrive (her last train in the project and the last train of the day), a J shows up instead. She asks if a Z is coming along and the conductor responds, “This J is the Z. / It’s the same train. / They’re all the same. / Get on.”

Written from 2017 to 2018, “My Quotidian Icon” covers multiple violences and is set against simultaneous crises. Landers expertly stitches together a complex portrait of New York City, from when the land was first taken from the Lenape to 9/11 and beyond. She covers numerous hurricanes, a recent murder, arboricides, and the casual violence of a bank buying the naming rights to a subway station, erasing the neighborhood and its history by seizing land through eminent domain to build a basketball arena. Landers notes that the bank/corporation had once been a family of enslavers, which is not an exception but the norm in the ruling class that does things like remove protections days before a hurricane arrives. The opportunistic cruelty is by design. All of these histories and details are deftly conveyed in short lyric lines that explore grief, connection, community, renewal, and recovery. It’s a poem about slowing down, reconnecting to the body, and paying attention: “the slow pace / of practice / sees in repeating / what went before it / unseen.” The poem also slips into the future, at times telling us more terrible news to come—a mass shooting in four years and COVID in two. Despite all the terrible events, the city continues: “And yet somehow / I still have faith / there will always / be another train.”

The second poem in the collection, “Sidewalk Naturalist” continues the work of the first, but here Landers is focused on the nature of the city and recovery. The poem is more spacious than the opener—frequently featuring multiple line breaks between lines of text and words spread across the full field of the page. Tree and plant names populate the poem, showing the diversity of Brooklyn wildlife as the author learns to identify various species. Landers details her productivity running out, the need to quit and rest, and eventually the wish to return to the world in some useful way, which she does by volunteering at a food pantry. She also makes an active choice to move toward beauty—noting the trees and flowers blooming in Brooklyn and suggesting that heightened awareness can help us through the aftermath of continuous crises. She notes, “Holly says sobriety / is paying attention,” and Landers does, slowing down, practicing intentionality, and focusing on one thing and then another. Nevertheless, the poem is interrupted by terrible news, written as a quick list: “Buffalo // Uvalde // Roe,” and Landers asks, “How do I write // about rest // in distress?” The poem acknowledges that people learn to live with pain, as few ever have the opportunity to rest and fully recover, and Landers is learning how to be at home “in the gravity of it all.” Despite this, the poem ends on a hopeful note, and a call to the book’s title, insisting “Every day // we choose // what to carry // into the future.”

The final section of the book, “Water Finds a Way,” is made up of alternating prose blocks and 14-line poems, a set for 14 different waterways in the city (though there are 15 sets, with the Atlantic Ocean both opening and closing the series). The first prose block begins with a quote from Lucille Clifton: “in water, the past is always flowing.” Landers tours the waterways, many of which are brownfields and superfund sites due to decades of pollution, and comments on the violent history of the city, from the prison barge on the East River to predatory real estate practices, environmental racism, and the housing of refugees in tents on Randall Island. She notes how the ecosystems are resilient, still populated by wildlife and serving as gathering spots—the creeks and rivers find a way, as the title of the series says—despite the damage done to them by humans.

Like Odell’s How to Do Nothing, Landers’ What to Carry Into the Future is an invitation to slow down, take a look around, and allow yourself to think outside of the demands of capitalism and productivity. Landers evokes the diversity of New York’s neighborhoods and populations—and illustrates diverse ways to love the city in all its complications. The collection serves as an important reminder in 2025, as workplaces “post-pandemic” forced the “return to normal,” which has meant the return to the office, unrealistic productivity, and the threat of AI taking people’s jobs among fewer worker protections. In a time of ongoing grief from multiple, ongoing crises, what if we paused instead of pushing through our days? What can noticing the world around us, instead of hurrying through our days and our commutes, teach us about living? Will the people—like water—find a way?

Gina Myers is the author of four books of poetry, including Works & Days (Radiator Press, 2025) and Some of the Times (Barrelhouse, 2020). She lives in Philadelphia where she co-edits the tiny with Ebs Sanders and Cul-de-sac of Blood with J †Johnson.