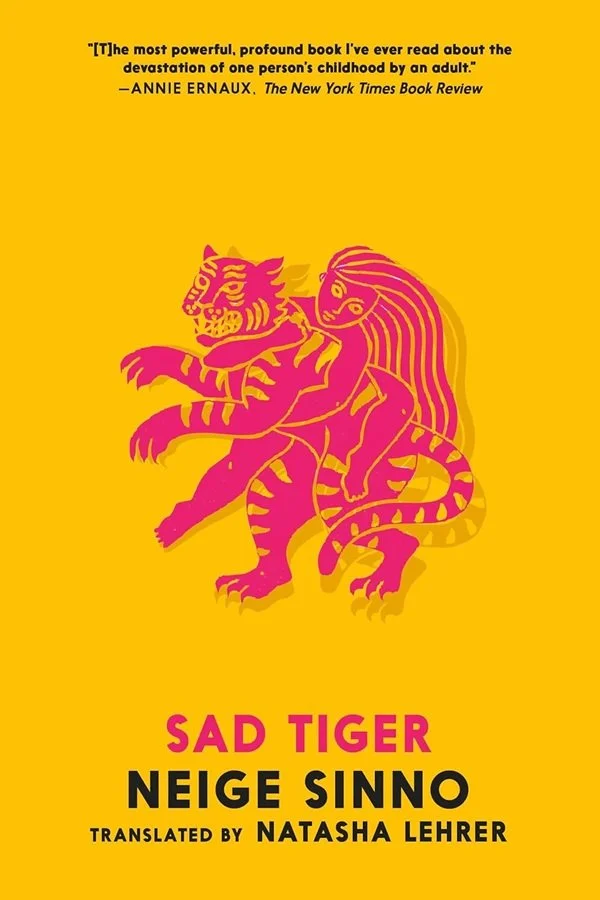

Barrelhouse Reviews: Sad Tiger by Neige Sinno

Reviewed by Ellen Kirkpatrick

Seven Stories Press / April 2025 / 288 pp / Translated by Natasha Lehrer

Content note: This review engages with themes of sexual violence, trauma, and the complexities of recovery.

“Tyger Tyger, burning bright…”

William Blake’s poem conjures a creature both mesmerizing and terrifying. This duality pulses through Sad Tiger, Neige Sinno’s searing account of prolonged childhood sexual abuse by her stepfather and the intricate, years-long reckoning that follows. Originally published in French in 2023, Triste Tigre swept major literary prizes (Prix Femina, Goncourt Prizes, European Strega). Natasha Lehrer’s English translation landed in 2025, and it’s not just timely; it’s timeless in the way only books that refuse to flinch can be.

In a landscape saturated with trauma memoirs, many narratives follow a similar script: a descent into suffering, followed by a redemptive arc, closure, catharsis. These stories often invite sympathy, offer spectacle, and lean into shock—sometimes at the expense of complexity. Society rewards this structure: it’s legible, comforting, and easily consumed. But it can reduce the lived experience of trauma into something palatable, even marketable.

Neige Sinno’s Sad Tiger resists that mold. It recounts her experience of childhood sexual abuse at the hands of her stepfather, and the ever-looping aftermath that reshapes memory, language, and self. But it refuses to perform healing or offer resolution. There’s no neat arc, no redemptive glow. Survival here isn’t found in acceptance or mastery, but in the messy, persistent act of questioning—an unfolding process, never concluded. Its elliptical structure invites a layered reading, moving between portraits of key figures, archive materials, and plainspoken reflections and meditations, by turns fearless and fragile. The narrative (still resisting summary) is ragged, recursive, volatile: unputdownable. A palimpsest of haunting fragments: intimate and often hard to bear. Provocative in the fullest sense, they demand engagement, not just attention. Among them:

Portrait of my rapist. Portrait of a nymphet. He has his good qualities too. My life as a horror film. Reasons for not wanting to write this book. Gray area. Shame. What to do with what was done to us.

Sinno writes from the ruins—a place of pain and paradox, where memory falters and language itself is suspect. Her voice flickers, probing not just her past, but the very act of telling. The result is a poetic confrontation with institutional failure, the limits of justice, and trauma’s enduring residue. A moment of radical truth telling that resists moral clarity, challenging readers to sit with discomfort and witness without demanding transformation. These are the stories that feel alive—in flux, unfinished, and honest to the bone.

It’s that raw vulnerability, sharpened by formal defiance, that rips through genre conventions, pushing Sad Tiger into terrain stranger and more urgent: a study in ambivalence, an excavation of fragmented selfhood, a critique of choice, of consent, or perhaps even a literary act of resistance. The story swells and fractures under the weight of what it holds, spiraling like trauma—scratching at scars, eating its tail, refusing to settle. The form is the message: trauma doesn’t move in straight lines, nor does recovery.

That fractured form demands a translator who can hold its tension without smoothing its edges, and Natasha Lehrer does just that. Having listened to Sinno speak about her work, it’s clear the English version carries her voice with clarity and care, remaining fiercely loyal to its rhythms. The jagged lyricism, the luminous emotional core, the refusal to shape trauma into coherence or comfort—all survive intact. The translation preserves the rupture, and in doing so, becomes an act of witness in its own right.

That sense of witness extends beyond Sinno herself. Her narrative moves between external confrontation and internal struggle, tracing the entanglements of those bound to her trauma—her mother, her biological father, and most centrally, her stepfather, who is also her abuser. No one is spared, but no one is flattened. Her stepfather, a mountain rescue hero, is rendered in full contradiction: a predator cloaked in the guise of a “good guy.” Her mother, too, is drawn with complexity: loving, complicit, broken. These portraits aren’t just character studies—they’re emotional autopsies. There’s no pretense of perfect memory, no perfect victim, no perfect monster, no perfect ally. Just people, caught in circumstances, shaped by choices, in the wreckage of what can’t be undone.

Sinno exposes the contradictions—within families and society—that allow abuse to flourish: love and fear, admiration and dread, silence and complicity. As she turns inward, the narrative shifts, to how trauma rewires the body and the self, fractures the past, and strains the machinery of language. Not just as vocabulary or syntax, but as the very system through which meaning is made, the space where silence is named and power reclaimed. Language here isn’t neutral; it’s contested terrain. “Because I was raped,” she tells us, again and again, a passive refrain that doesn’t obscure but insists, marking the collapse of agency, the suspension of free will. This isn’t about what the rapist, her stepfather, did; it’s about her, what was done to her—her compromised agency, her altered reality. Survival isn’t triumph. It’s endurance. The quiet quake beneath everything.

What cuts deepest is the book’s refusal to stop at the subject, pressing forward into the reckoning, the ache that outlasts the event. Sinno indicts not only individuals but systems, unsettling what we think we know about sexual violence and the aftermath. Looking beyond the fractured self, she interrogates the vast cultural and literary scaffolding that shapes how such violations are understood. These references aren’t name-drops, they’re lifelines. Nabokov’s Lolita, Annie Ernaux’s memoirs, and Virginia Woolf’s essays unravel the myths of consent and control, and become part of her reasoning. Through them, and many others, she questions the desirescape of sexual abuse, the ontology of silence, and the ethics of storytelling. Literature, she insists, is both weapon and witness.

Sinno reads to survive, to resist, to understand. (Don’t we all?) That’s why she writes, too. But she doesn’t just write—she interrogates the act of writing itself. What does it mean to narrate the unspeakable? Can literature bear witness without aestheticizing pain? Can story save us? Make us stronger?

And what even counts as story?

Sad Tiger unfolds through many kinds of storytelling: trial transcripts, letters to the police, newspaper clippings, conversations, fairy tales, descriptions of photographs. These fragments aren’t just supplemental; they’re structural. They form a constellation of voices, perspectives, and registers that resist coherence, subtly revealing the power relations embedded in who speaks and how they’re heard. By interlacing multiple forms of expression and embracing fragmentations, Sinno resists privileging any single way of knowing. She offers not answers, but a form of witnessing—one that honors complexity, and holds space for what resists being named. This is silence-breaking not with capital-T truth, but with the kind that lives in the body, in memory, in the spaces language strains to reach: the grain of a voice, the weight of omission, the rub between what’s remembered and what’s recorded. In this way, Sad Tiger becomes not just a memoir but an archive and vanishing point: a space where different kinds of perspective coexist, collide, and complicate each other.

And there’s something deeply human in the messiness of it all—the inconsistencies, the unresolved questions, the repetitions, the silences, and the endless search for meaning, for agency. They’re what make the book feel meaningful and nourishing. It’s not therapeutic or didactic, but then again, it’s not trying to be.

Sad Tiger is a howl against the silencing of pain and the grinding down of survival into something digestible. It’s not an easy read—nor should it be. Its power lies in its unresolved honesty, its formal daring, and its refusal to tame trauma. Few books confront so fiercely, or resonate so deeply. Sinno asks readers to face the violence that hides in plain sight and to reckon with the limits of language, memory, and justice. Sad Tiger shows what it means to bear witness through words, fangs bared, stripes unhidden.

Ellen Kirkpatrick is a writer with a PhD in Cultural Studies and a passion for (counter)stories. Based in the north of Ireland, she writes mostly about pop culture, radical imaginaries, and the transformative power of story. Her book Recovering the Radical Promise of Superheroes: Un/Making Worlds was published by punctum books (2023). Ever curious about wild worldmaking stuff, Ellen is currently working on a book-length essay about time, place, story, and self, tagged reveries of a lush year in a troubled land.