Letters to the Editor, by Josh Krigman

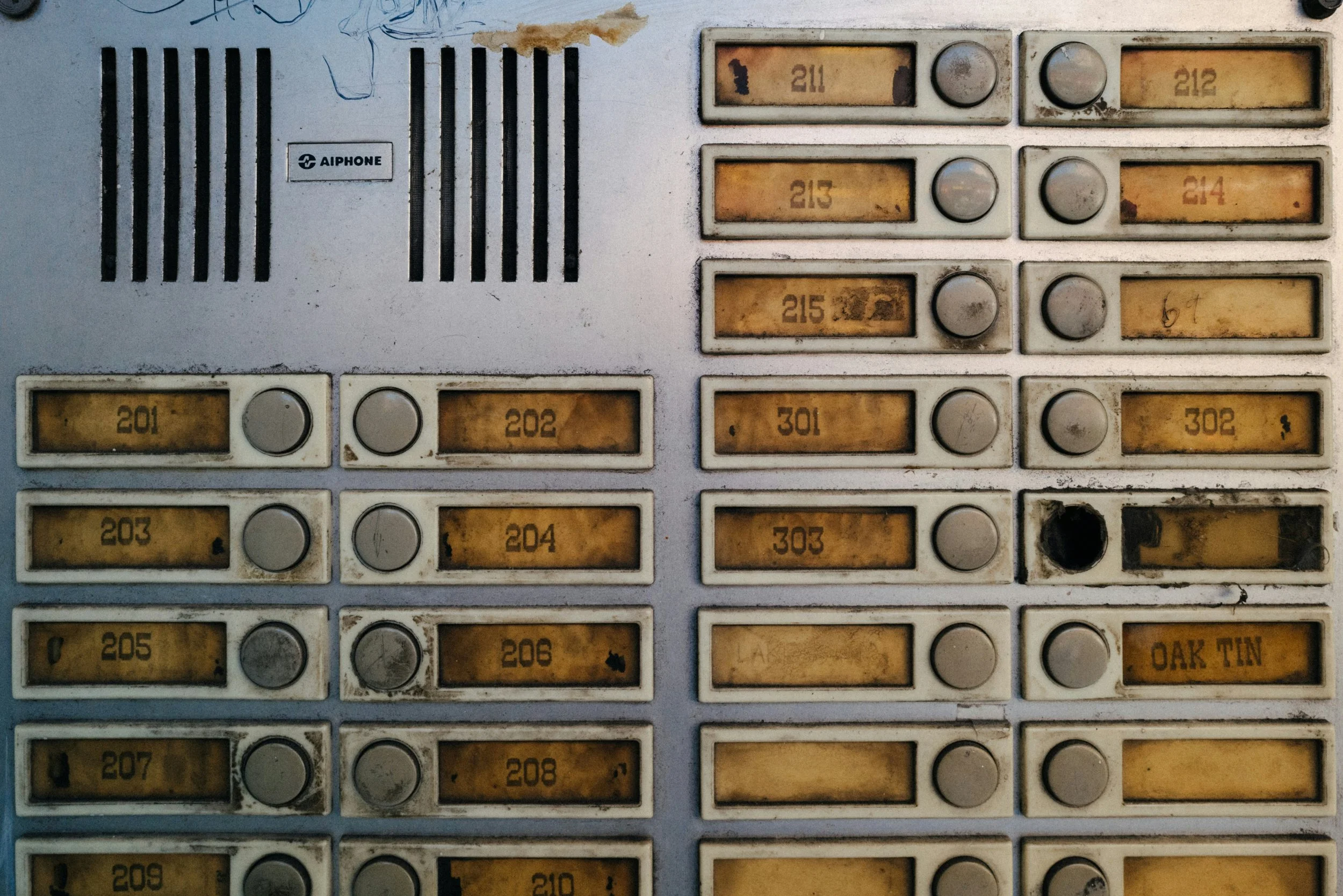

Photo by Zane Winter

When is a sidewalk a storefront? This is the question I ask the readers of the Providence Post, a paper I have read loyally for over 40 years.

The answer is never. A sidewalk is not a place for doing your business. It is a place for walking. A place where you can walk to the side of the street, so you don’t have to walk in the street and end up like my nephew Jacob the cripple.

If a sidewalk were for doing your business, it would be another word. Maybe sidestore, or salepath. This is a nice feature of English. You can look at a word and see what it means. Headboard, bookcase, stovetop. The meaning sits on the surface, like a matzoh ball. A matzoh ball is the same in the middle as it is on the skin. There is no hidden center. You know it by looking. You can cut it in half and what do you find inside? More matzoh ball. In this way, you can know a sidewalk by looking at the word.

You are thinking, oh dear, why such a tizzy? Let me say more.

In the mornings I leave my apartment—the one, please know, where I have lived since 1977 as a law-abiding citizen, unlike some other goyisha nudniks I know—and go to Leo’s Deli on Cypress and Courtland to get a cup of coffee and the paper. This paper. And for the last eight mornings there has been a store set up on the sidewalk outside my front door. I am forced to walk in traffic to reach the end of my block! There are books and records and old clothing that hangs from a rolling tin rack. There is a bridge table stacked with dirty ceramic dishes and bowls. When did Providence become a shantytown? A yard sale is one thing, but please, look again at this word. No yard, no sale.

There are many laws about this problem. But what good is a law if it is not enforced? I called the police and they laughed. For the rest of the day I think maybe they are right. Maybe I am another old man making silly complaints. Maybe I am the crazy one. Then I walked outside and slipped on a National Geographic and nearly broke my neck. For shame! So I ask my question to the Post: What good is a law if no one follows it? What good is a sidewalk if it is filled with mishigas and I am forced to walk in the street? It is nothing. Something must change.

—Joseph Moscowicz, 6/4/2014

*

I was charmed to read Mr. Moscowicz’s letter in Wednesday’s Post. I am familiar with the issue he references. However, instead of finding it a nuisance, I consider these vendors an enriching part of our neighborhood dynamic. Providence is a metropolitan city and, as a result, replete with a myriad of lifestyles. It is both natural and appropriate for the city’s many thoroughfares to reflect this.

Mr. Moscowicz cleverly dissects the meaning of ‘sidewalk’ while completely disregarding, willfully or through ignorance, the reality that language evolves, and our perceptions must evolve with it. While a sidewalk is designed as a way for pedestrians to traverse the streets free from the dangers of motor vehicles, it does not serve this purpose exclusively. It is also public property, and a shared space for citizens to integrate themselves with the community.

Would Mr. Moscowicz have us refrain from exchanging pleasantries when passing an acquaintance on the street? Surely this stationary dialogue would impede his ability to maneuver what I imagine must be the most narrow sidewalks in all of Providence? What of trash cans, mailboxes, and newspaper dispensaries? Shall we eliminate these as well? Or the children, riding their tricycles, no doubt weaving back and forth and obstructing Mr. Moscowicz’ path. Do we cast them into the street so he may travel at the speed to which he is accustomed? Following the precedent Mr. Moscowicz has set I will answer my own question: No, we do not.

I have a small stand of the variety Mr. Moscowicz references. I am an older man, and live off what the government has deemed appropriate to return to me after my many years as a Professor of Anthropology at Brown University. I too have lived in my apartment for close to four decades and, as a result, have accumulated a large wealth of possessions no longer necessary in my old age. Instead of discarding them, I have chosen to recycle, and pass along these goods to those in need, at a bargain price. A young woman acquires a lamp and I earn a few extra dollars to put toward milk and eggs. A criminal I am not.

I recommend Mr. Moscowicz wrap his scarf a little looser, and not conflate decreased sidewalk space with felonious activity. While it was wrong for the authorities to have openly expressed amusement at his complaint, it was also wrong of him to assume they would spend time and taxpayer’s money on such a non-issue. A sidewalk contains more than Mr. Moscowicz’ surface read of the linked words comprising its form. Sidewalks are the cultural seams that stitch together our public and private life. Policing them would only serve to censor that which makes this city so beautiful. I am confident there will always be a clear path for Mr. Moscowicz, wherever he is headed, as long as he’s willing to look in the right direction.

—Prof. Arthur Bailey, 6/9/2014

*

In his responding to my first letter, my upstairs neighbor Mister Associate Professor Bailey makes many interesting points, and they all point right in the toilet. This is also where I think he stores his coats when he is not hanging them outside my window.

If a sidewalk is public like he says, why can he do his private business on it? Where is my cut, Mister Communist? Why not give those few extra dollars to the dynamic neighborhood you love so much?

Since my last letter, Mister Communist Bailey’s stand has grown to the length of our entire building. It is like a dirty hand stretching its fingers farther every day. I hear him lugging his crap down the stairs, each time more than the last. The only sidewalk left free is a thin piece of cement between the front of his tables and the curb. I am not one of those skinny-hipped ladies in the tight pants who jogs on the street night and day. I am an old man. Somewhere, in the last few years, one leg has grown shorter than the other. I need a full sidewalk. Is this so wrong and unusual?

Mister Professor tells you he is worried about the children on the tricycles riding in the street. But they already ride in the street to get around his tables! Many years ago, when my nephew Jacob the cripple was only Jacob my sister’s boy, I was walking with him on Oakhurst when a driver who did not see us hit him with a Volvo. He has been in a wheelchair since this day. I do not need lectures on children in the street. I need the sidewalks empty of non-sidewalk business.

I also do not need lectures on evolving language, like I am one of his weak-in-the-face students from the university. I speak a bastard language born from all the places my people were made to leave. It has evolved in more ways than books can teach.

As for the tightness of my scarf, it is fine the way it is. If you want to make room on the sidewalk for one of these acquaintance meetings you like so much, I will show you where the stitches are, you soft-handed putz.

— Joseph Moscowicz, 6/13/2014

*

I have spent the weekend contemplating the many insults and threats my neighbor Mr. Moscowicz has directed toward my person, and against better judgment have decided to reply. My soft hands, as he calls them, have been forced.

I am not a communist. I love my country, and have my entire life. I will not be cornered into defending against this ludicrous claim, though it is worth pointing out that accusing someone of abusing both communism and capitalism in the same breath is absurd, and unworthy of the paper on which it is printed.

I would also like to apologize to the readers for embroiling them in what is, and I expected to remain, a private matter. I have known Joseph since 1979, when my wife Rose and I moved into the apartment above him and his wife Sarah. Rose and Sarah were great friends, and for thirty years my relationship with Joseph was the by-product of their affection for one another. Married readers of the Post will understand. Rose passed away two years ago this winter, and I suspect Joseph is now treating me with the feelings he has harbored all along. My table is not as large as he claims, nor is it like a dirty hand. It works to offset the rising price of the medicine on which I find myself increasingly reliant, and, as I have previously written, is a contributing factor to our neighborhood’s character. That his personal distaste for me has been brewing for decades and only now has the freedom to surface is the only way I can explain his offence.

I hope this letter finds Joseph well, and that whatever issues may arise between us no longer need include the whole of Providence.

—Arthur Bailey, 6/18/2014

*

The type of a man it takes to cry privacy and then drag thirty years of history into the street, like one of his rusty tables. I count this among the many things I will never understand no matter how many years God gives me.

I never disliked Mister Bailey. Were we close? No. Always a little removed, this one. A little above. But was this such a bother? No. I was a cobbler on Bainbridge and Ninth for 38 years. I am used to seeing people from the heel up, and the way they look down like we are both where we belong. So Mister Bailey’s ways were not taken with offence, and they are not the reason for my complaining about his tables.

The truth is it is our history that almost stopped me from saying anything. We are neighbors, and such complaints are not a neighborly thing, especially when we have already shared so much. Many times did I sit in this man’s home, the women like schoolgirls, talking close, like the sound of their voice was a secret. He and I were not so chummy. We were nice.

When you live so close to a person—a little wood, a little plaster—you are part of their life. There is a special bond, no matter how you like them. After Rose died, it took no thinking for me and Sarah to be there, even though this was when she was already sick. We came into their home and we sat shiva. We wept. Then, last spring, Sarah breathed her last and again became one with God. I was both empty and heavy for days. My family and friends came and joined me in my grief, and then they left.

Where were you? A few feet above and not even a card from Mister Professor of Anthropology. The study of people my foot. I have eaten dinner in this man’s home. We have broken bread. Is anything more sacred? It doesn’t matter how you get along. When a man’s wife passes away you come say a prayer with his family. It is he who abandoned the bond between neighbors, and so I respond like he is anyone else. Another shmuck on the street with his junk.

—Joseph Moscowicz, 6/23/2014

Josh Krigman (he/him) is a writer and teacher in New York City. He has been awarded residencies from Vermont Studio Center, and his work has appeared in The Summerset Review, Akashic Books, Necessary Fiction, and elsewhere. He received his MFA in fiction from Hunter College. He is also the founder of Little Nights, an arts programming series that hosts interdisciplinary events and creative retreats.