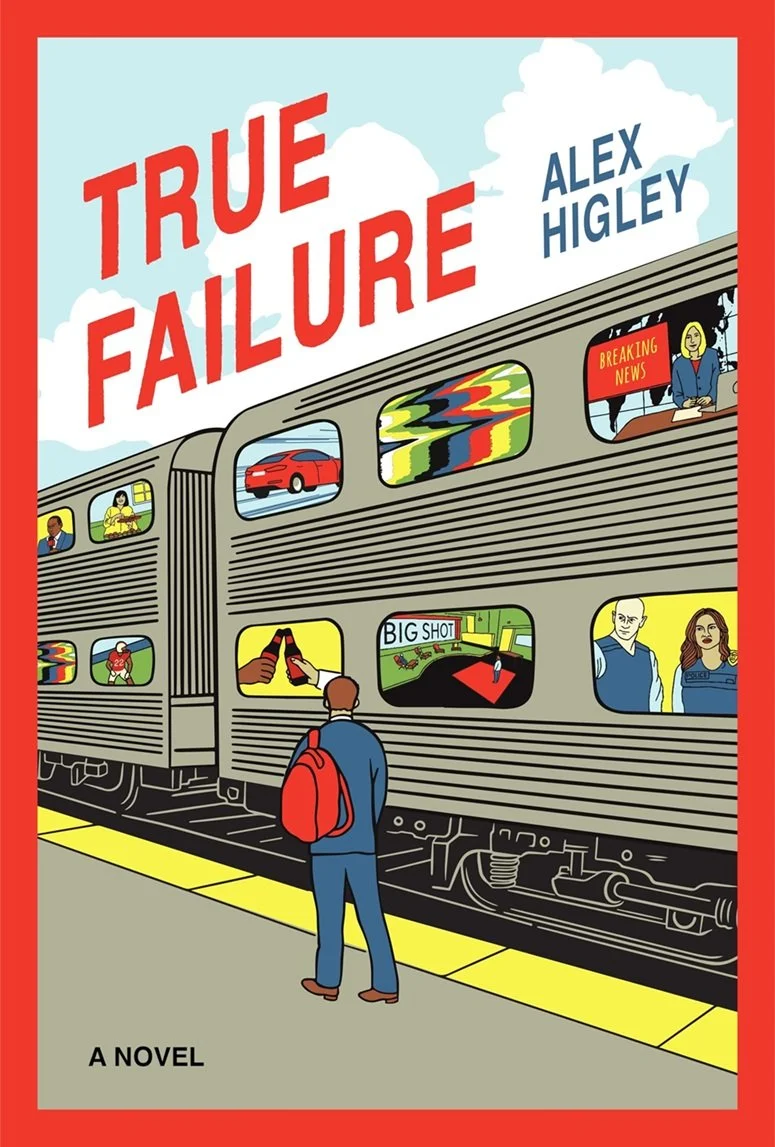

Barrelhouse Reviews: True Failure by Alex Higley

Reviewed by Milan Polk

Coffee House Press / February 2025 / 280 pp

Alex Higley’s True Failure centers Mariska Hargitay as a god-like figure. The main character, Ben, is a thirty-something, recently fired accountant who spends his days lying to his wife about his joblessness and hiding out in the local library, binging episodes of Law and Order: Special Victims Unit. He’s in awe of Hargitay and how she relates to her iconic role as Olivia Benson. She’s “Beautiful, but not oppressively so. Older than she looked. Familiar.” In another life, he thinks she could be the perfect contestant on Big Shots, a Shark Tank-like show Ben is also obsessed with. Bogged down with debt and avoiding all responsibility, Ben’s new goal is to appear on Big Shots and make a successful pitch, whatever it takes.

True Failure begins with Ben, but the book’s omniscient narrator pops into the heads of other characters as well, namely Ben’s wife Tara, Big Shots casting director Marcy, and her two interns Brent and Callie. In Ben’s quest to appear on the show, his determination places pressure on the surrounding characters, their own goals, and how they too are willing to go to extreme lengths to gain what they want. At the heart of True Failure, Ben and those around him are silhouettes of young adults today–feeling societal pressures around aging, marred by the economic barriers of the current decade–who are desperately searching for meaning and purpose when milestones seem to elude them.

Ben and Tara are plucked straight from reality; they have a house with a mortgage, student loans, credit card debt, and hope to soon have a child. But Ben’s firing is a setback. It means he has to face “the reality that he was no longer employed, had no real prospects for the immediate future, and frankly could account for less of what had happened to him than was acceptable for a person his age; he lacked answers to questions he had never even thought to ask.”

It's worth questioning what exactly is "acceptable" for someone Ben's age to be accountable for; his malaise goes far beyond a sense of delayed gratification or general boredom. Millennials and Gen-Z workers film themselves getting laid off these days, and both generations' career spans face instability due to political and economic uncertainty. Five-year plans aren't as certain when job-hopping is now seen as the best way to move up the ladder. It's harder to find purpose or stability when nothing around you feels solid. And so Ben turns to Big Shots and SVU.

True Failure taps into a poignant moment of delayed development, that liminal stage in one’s late 20s and early 30s of waiting for something, anything to happen. While Ben could deal with the underlying problems of his marriage, or search for a new job, he instead decides to play into a flashier type of late-stage capitalist success advertised to him. Staying the course has gotten him nowhere, so it makes more sense to take the more drastic, fickle path and pitch a product to wealthy investors.

Higley bounces between character perspectives. The disjointed narrative provides a window into the characters' yearning via structure as well as characterization, and with each added viewpoint (Tara, Marcy, Brent, Callie), the reader hopes for a shift in any one character's malaise. At least one of them must succeed, right?

For instance, Callie, Marcy’s intern, budgets for outings at Target, and her mother pays for her Los Angeles apartment. And yet, she imagines a future in New York, working at Good Morning America. She wants “A husband with a career like dentist, actuary, financial planner, dermatologist,” and to move back to her hometown, the Twin Cities, so she can brag to moms on the playground about her former life working in television. But for now, she has no relationship, no future career prospects, and no sign of anything changing anytime soon. To pass the time, she listens to true crime podcasts and creates fictional detective work for herself. Until something better comes along, this is her reality. When we get Callie’s perspective, she acts as an observer, reacting to the world around her more than engaging in it. “Callie was typing on her phone while listening to Marcy, performatively engaging with the words Marcy was saying as they were being spoken—not really listening, but it was the expected style of conversation in this moment, the notation, confirmation, searching.” Outside of her boss and coworkers, Callie only speaks to her mother; we don't hear from friends or anyone else beyond the building manager at her apartment. Our brief moments inside Callie’s head feel less like a character arc and more like social commentary; she’s a lonely Gen-Zer who spends more time on her phone and in her head than actively going for what she wants.

The novel's use of introspection for each of its characters successfully demonstrates the isolating features of late-stage capitalism. Rising costs due to inflation, precarious job prospects, and our increased reliance on technology for social connections means it's daunting to make friends, network, or find romantic prospects. Ben mourns the diminished relationship with his ex-coworker, and holes up in the library to job-search. “He stood in his nook at the library, took off his tie while several other jobless library regulars noted his standing, noticed an unblinking librarian watching him from ten feet away, and sat back down.” None of his fears are shared aloud or acted upon.

True Failure's characters wrestle with their usefulness. Everything they do must serve as a means to an end; their actions must produce something valuable. Tara’s perspective says as much: “Yes, Ben had a job, but it was not enough. They needed to maintain two incomes like everyone they knew and everyone else those people knew. Student loans and a mortgage, credit cards, those three to begin, and need it even be said?” Ben's rejection of this notion—through stalling his job search and betting his hopes on a TV show appearance despite no product to pitch—creates a ripple effect among all involved in his pursuit.

Post-college, Higley asserts, the looming shadow of debt and potential joblessness stands in the way of self-discovery. The other characters in Higley’s novel find Ben’s desire to be on Big Shots silly and hopeless, but his endeavor indicates the mythical American Dream vanishing in front of young people’s eyes. Adulthood before age 35 has become a period of life separate from what might be considered a “full adulthood,” as it’s no longer a personal choice for many to live in a city with roommates or buy a house, to have children or not, to hold a job that ensures promotions and salaries or to jump around. The whims of the market decide, and all an early adult can do is hope to find a new way to reach those dreams.

Within the confines of a novel, Ben and Higley reckon with the instability contemporary life brings. Ben seeks to avoid the traditional path to adulthood even as he bewilders everyone around him. Rather than searching for a job to continue the career track he’s on, Ben utilizes Big Shots as his opportunity for reinvention. It’s not really about the pitch or the money that goes with it. He wants to appear on the show so that he can fast-track his way to the feeling of success. When he finally does land on an idea, Ben excitedly pitches to Tara his hope to bring Big Shots to their fictional town of Harks Grove, Illinois: “I don’t have an idea; I’m using their idea. I want them to give me money so I can organize my own Big Shot in Harks. Local. Smaller, less profitable ventures that aren’t designed to make me money but instead help the community. Help the community thrive.” Tara swiftly brings him back to reality: “You don’t wave to the neighbors.”

Between Mariska Hargitay and Big Shots, Ben envisions a version of himself that’s self-confident and strong, achieving a comfortable stage of life and skipping the struggle. It’s an unlikely prospect, but the novel aptly echoes reality and the hurdles those under 35 face. Higley offers up his five characters as blatant archetypes to the Millennials and Gen-Zers struggling right now. As late-stage capitalism further entrenches itself in every aspect of culture, it only makes sense that there are novels that bring us face to face with its consequences.

Milan Polk is a culture writer. Her work has appeared at ELLE, Men’s Health, and elsewhere.