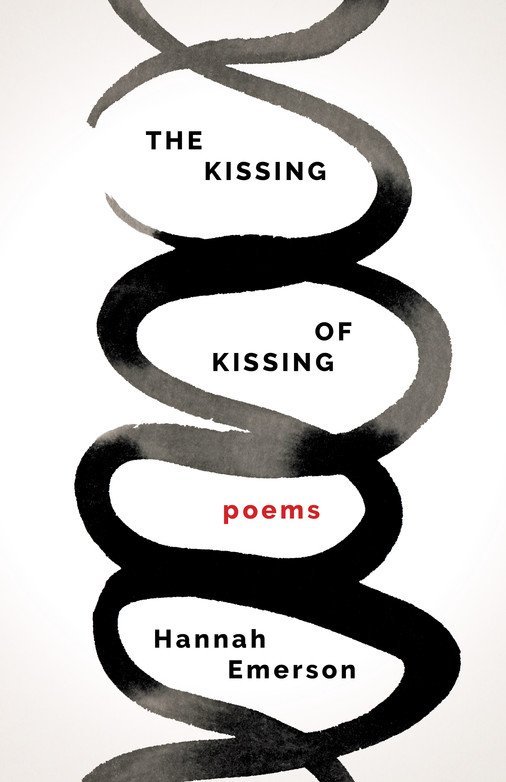

Barrelhouse Reviews: The Kissing of Kissing by Hannah Emerson

Review by [Sarah] Cavar

Milkweed Editions / March 2022 / 112 pp

Yes yes.

The Kissing of Kissing is a bodymind-in-motion. With Kissing, Emerson, a nonspeaking autistic artist and poet, inaugurates Milkweed’s Multiverse series, which will center neuroqueer orientations in relation to writing (and) the world. In spectacular bursts of movement and color, Emerson lives the gamut of autistic feeling. These poems, which blur the boundary between flesh and text, body and poem, affirm the collection’s opening demand: “Please get that great animals are all / autistic. Please love poets we are the first / autistics.”

In Kissing, the act of kissing is not only a discrete, intimate act, but an epistemic approach that structures Emerson’s life and work: “Please / get that kissing mind needs us / to kiss knowledge yes yes.” Here, to associate knowledge exclusively with “the mind” is hopelessly reductive. Instead, Emerson’s associative, unpunctuated, and perpetually-surprising wordwork recalls a body that thinks, feels, and refuses to sit still –– a body whose thoughts pour out in flaps, twirls, and echoes, each movement a kiss. These ways of kissing-into-knowledge appear in the first lines of “My Name Begins Again,” the collection’s first poem: “No Hannah oh I want / to make my life like / my name.”

Kissing could itself be considered an act of self-naming, and the text a counter-diagnostic effort against ableist conceptions of autistic “emptiness.” In truth, autistic reality is far from empty –– Emerson conceptualizes autism as a “bridge / between the worlds”—that is, between a neurodiverse assortment of humans and nonhumans, flora and fauna. What does it mean, she asks, to bend-speak the language of trees, of bears, and of human beings? To wield at once words, lips, and hands? Emerson belongs to a story of abundance.

Yet institutional ableism remains, and Emerson does not shy from its violence. She alludes to ableist violence, and specifically to penal, carceral approaches to autistic ways of being, in her discussion of “hell.” She asserts that hell is “what we are now now / now,” While unequivocally harmful, hell, for Emerson, is also not without light nor hope: “Please try to go / to hell frequently / because you will / find the light there.” Hell is not a destination, but a starting point from which new worlds might be born. Hell is made of red-hot stone waiting to come to life. Emerson’s writing opens the underworld like a womb or room, making space, and “growing into the steam / of molten life yes yes.”

Yes yes. This is a lively text. “Love love is just flapping,” Emerson writes, and Kissing is thick with flapping hands and kissing (e)motions, yes yes. This oft-repeated phrase anchoring the collection, as well as other doubled words, achieve distance from their pathologization as autistic “echolalia” and resignify as essential to the art of autistic being. Further, “yes yes” echoes a familiar cry of sexual ecstasy, but extends far beyond normative expressions of sexual pleasure. Instead, Emerson introduces a pleasure far more difficult to pin: one tied to practices of unabashed, gratuitous selfhood, of “beautiful needing being.” Kissing understands knowledge not only as something to be cognitively known, but also to be felt, to be tactile, to be intimate, to be stripped. To be an autistic poet is to be and know from the “gutter.” To speak “all / guttural guttural yell / yes yes yes.”

The epistemology of kissing also blurs pedagogy, pleasure, and communication, evoking an erotic project reminiscent of Audre Lorde and based in collective, embodied intensities oriented toward transformative change. Indeed, Kissing articulates nascent worlds anxiously awaiting their opening. The text repeatedly calls upon the reader to challenge our perceptions of embodied and enminded difference. It conjures generative opacity with its vibrant, tactile verse; the poem “Lovely Burst” opens: “Please free me free air to be / like you helpful kissing verse,” bending syntax in order to better know the burst, the verse, and the breeze. Emerson, as an autistic poet, is not broken in the face of neurotypical linguistic norms, but rather an agent in the breaking and rebuilding of alternative ways to know the world.

Moreover, Emerson is shameless, in the best possible way. Through practices of kissing, dancing, stimming, and echoing, Emerson articulates an “autie-erotics” of knowing that categorically refuses shame. “Please try to go to the party / naked do not feel ashamed / because we are our best / when we dream of a naked / kissing life without the stuff / that we become the stuff that / stops us from trying to dance / yes yes.” Nakedness not only refers to a shedding of the “masks” autistic people so often don in order to survive neurotypical social life, but also to free one’s bodymind from social pedagogies of shame. In this refusal of shame, Emerson dreams of entirely new worlds, calling upon readers to “Please try to help / the reality that is / trying to spring / into the flight / that is trying / to go to the sun / to make itself.” Each page of Kissing buzzes with potential energy only activated through unapologetic refusal to comply with creative, epistemic, and social norms.

There is art in autism. Autistic life is art. Emerson’s generative tangle with language reconfigures autistic bodyminds not as sites of emptiness, but as agents of creative transformation.

Emerson’s are poems in which words are not weapons, but LeGuinian carrier-bags; with each echoing affirmative –– yes yes –– we gather vital wor(l)dmaking tools. Likewise, Emerson’s words wander, stim, wonder, fly, kiss their way across heaven and hell, through knowledges both crystal clear or deliriously muddied. Throughout, we readers are held. We are invited to miss understanding, to fly, fall, and try again. And we are always always accompanied by the reminder: “you grow / into the freedom that loves you."

[Sarah] Cavar is a PhD student, writer, and critically Mad transgender-about-town, and serves as managing editor at Stone of Madness Press and founding editor of swallow:tale press. Author of three chapbooks, A HOLE WALKED IN (Sword & Kettle Press), THE DREAM JOURNALS (giallo lit), and OUT OF MIND & INTO BODY (Ethel Press), they have also had work in Bitch Magazine, Disability Studies Quarterly, Electric Literature, The Offing, and elsewhere. Cavar lives online at www.cavar.club and tweets @cavarsarah.